| Sociolingüística internacional |

Analysis of the term

‘pariente’ as a form |

||||

| CONTINUA |

|

It could be argued that these forms of address are innate to the language. In a linguistic process that supersedes the simple reference given to it by proper names, social and interaction marks of the subject who is immersed in a complex system of relationships, is used under the lexical variation of the pronominal forms. The most peremptory of these forms is perhaps the one that distinguishes between ‘natives’ and ‘outsiders’ which we will call markers of origin. (5) Starting with the general framework that has been sketched out regarding the forms of address in Colombia and encouraged by the previous thought, the question arises: In the Sikuani’s use of Spanish as language that is not their own, which forms of address do they use? Using a survey (6) performed on the members of the Sikuani ethnic group that live in the area of Puerto Gaitán, in the region of Meta, an attempt was made to tackle the aforementioned question. The social variation of ten informants between the ages of 15 and 55 (divided into two groups: ages 12-20 and 25 and older) were taken into consideration, most of which who had basic education levels and an optimum level of using Spanish. The questionnaire consisted of six general questions and one hundred specific questions regarding the forms of address in the different types of interaction that were asked in an informal manner (conversation) and also involved general information of the informant like their age, origin, schooling, etc. (7) The quantitative analysis of the situation in Puerto Gaitán produced the following data. The form most often used –and almost exclusively– is the ‘usted’ form used with the white man and in some cases among relatives and friends. This is probably due in part to the fact that the teaching materials and written texts that generally end up in their hands do not contain any other forms of address than ‘usted’ as we can see in the following examples. ‘Tú’ and ‘vos’ are mostly used in oral conversations:

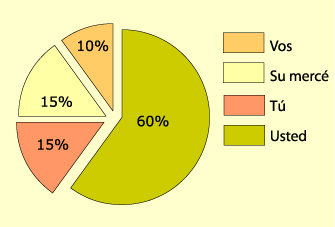

The forms ‘tú’, ‘vos’ and ‘su mercé’ are practically unknown for individuals who live in the community except for one or two who, despite demonstrating their knowledge of these forms, don’t use them because they don’t feel they are their own (see Fig. 2). Figure 2. Average use of forms of address 'vos', 'su mercé', 'tú' and 'usted'

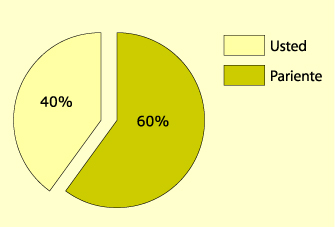

Figure 3. Average use of forms of address 'usted' vs 'pariente'

|